I’ve previously written about the Nikon D70. As I seem to have some affinity for older Nikon cameras, and as my D70 is also pretty beaten up, I couldn’t resist a good deal on a Nikon D70s with an attached Nikkor lens that has long been on my list: the Nikkor 35-70mm 3.3-4.5 AF lens. First released in 1986, the 35-70mm is most definitely a lens made for film cameras of the time as a cheap walk-around unit.

Some detractors say the focal length of 35-70mm isn’t especially useful on an APS-C sized sensor, but I disagree – 35mm is a popular wide, not not too wide, focal length, and 70mm can most certainly get you close or give you a decent portrait. Even if you consider equivalence (and a 50mm lens is still a 50mm lens on any sized sensor), the lens gives us 35mm eqivalent focal lengths of 52mm, 85mm, and 105mm – all three of them very useful lengths on any camera.

As for the D70s, it was announced in August 2005 and came hot on the heels of the original Nikon D70. The differences between the two models are minor, with the back-screen of the S iteration being 2 inches rather than the 1.8 inches of the original. The other features remain the same really: a 6.1 megapixel CCD APS-C-sized sensor, a top LCD screen with settings information, and an array of useful external controls, including ISO and White Balance, among others. Though it’s an all-black-plastic affair and has that familiar hollow feel of Nikon’s cheaper offerings, it definitely has a prosumer feature-set. Sure, the Nikon D200 is the professional upgrade, with a solid magnesium-alloy skeleton that feels like a giant warm buttered scone in the hand, but the D70s still remains a competent DSLR even in 2025.

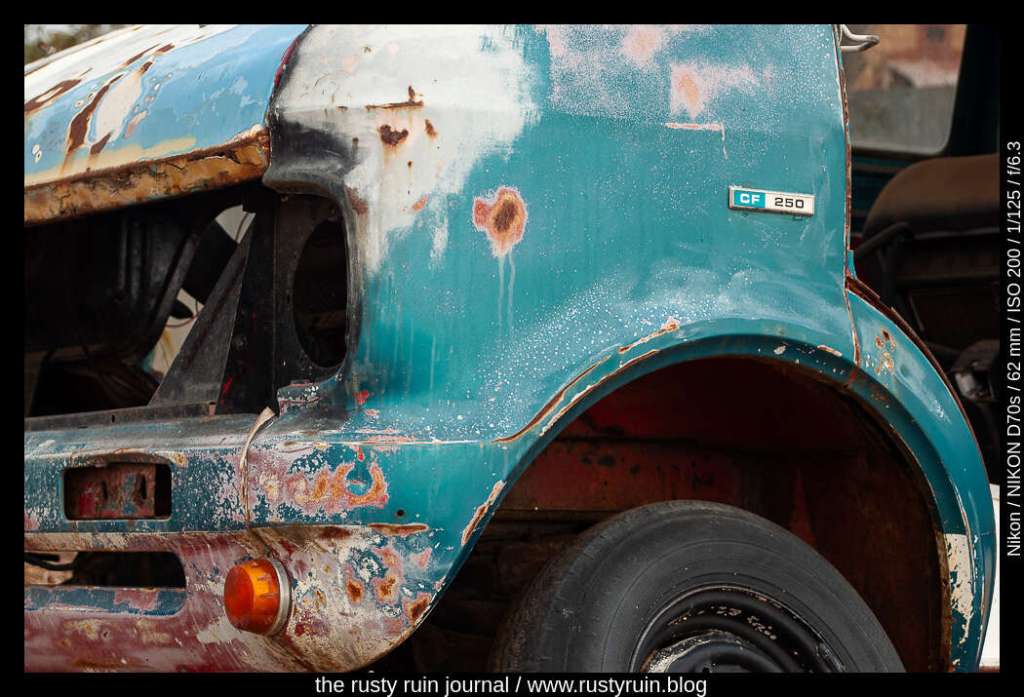

All the photos were made using the lens at F-stops 5.6 – 8. As you can see, the photos are sharp and punchy, even using a 6.1 megapixel sensor from yesteryear. Need I go on about the competent image-making capabilities of these older cameras?

I was helped by heavy cloud-cover, as there wasn’t a lot of dynamic range for the old CCD sensor to manage. Even though you can print pretty large from a 6 megapixel camera easily without much loss, the lack of cropping room makes one slow down and compose deliberately – there’s no running and gunning here. No lazy composition and fix it in the edit mentality. Old lenses, lack of high ISO, and fewer megapixels is good for getting back to the basics of photography: seeing clearly, connecting to the world through imagination, subject choice, composing deliberately, correct settings to suit scene and intent, and good hand-held technique.

If you print a 1 megapixel photo at billboard size, it will look like badly made bricks up close. If you stand 50 feet away instead, where just about everyone will be viewing it from, that 1 megapixel image will look pretty good. Viewing distance makes all the difference, and this is what we also need to consider when it comes to resolution and print sizes. Are you standing two inches away to view your photo prints? Even so, I don’t want to needlessly toss pixels away if I can help it, especially on these old cameras. I slow down, look, reflect, imagine, think through settings, check the histogram for exposure, and adjust if necessary.