We looked up at the huge rocky dome, in awe of the ancient geological processes that had created it. Over 500 million years ago, before dinosaurs wandered the lands around the ancient sea that would one day become a national park and tourist attraction, Uluru and Kata Tjuta started to form. At such times, you realize the scale of the world around you and feel very small indeed.

Doing the 10km base walk is the best way to appreciate the vastness of Uluru. We were already exhausted from our 8km hike through Kata Tjuta the day before – those rocky slopes and winding pathways can be unforgiving on cheap hiking shoes! I once climbed Uluru in about 45 minutes, back when it was commonly known as Ayers Rock. No-one is permitted to climb it now, but you can still see the old climber’s entrance and the worn path that millions of tourists braved over the years.

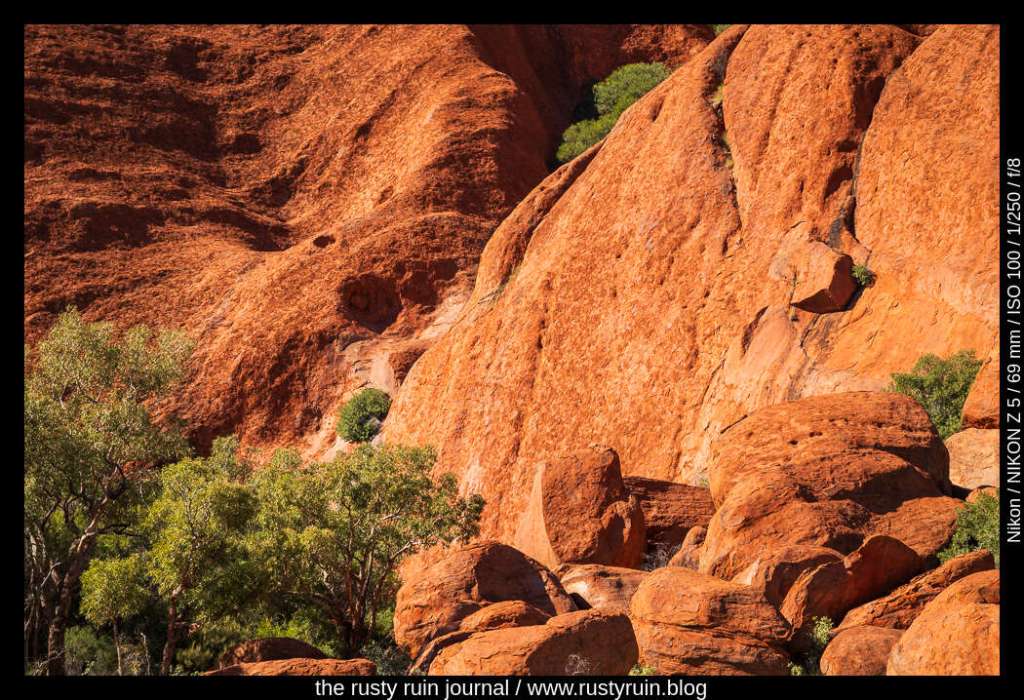

From a distance, Uluru looks like it has quite a uniform surface, but up close is where you get to see the details – weathered sections of grey stone, streaks of white, dark caves that seem to make recognisable patterns, and the iconic red rock that signals high iron content. Both Uluru and Kata Tjuta were formed over millions of years as the soft parts of the Petermann Ranges were eroded, leaving only the boulders and rocks.

Uluru takes on different colours, depending on the time of day and season. It can be bright orange at sunset one moment and then pink with purple and blue shadows the next. I posted a sunset picture in another post, though it was a rushed pull-over to the side of the road and the local police weren’t too happy we’d parked in a no-park area as they beeped us on a drive-by! You take your chances when you have a camera in-hand. There are some designated photo spots in the area for tourists, but they can be quite busy, and I’m not always best pleased to make photos that everyone else does.

I was more prudent in my use of the circular polariser on this trip. Hiking around the base of Uluru, I was mindful of the location of the sun. The polarising effect is strongest when the sun is at a 90-degree angle to where you’re pointing the camera – so either on your left or your right. I dial it up so that the effect is strongest, and then dial it back a bit to add more natural stray light reflections back into the scene.

A polariser is fantastic for cutting out stray reflections on foliage and rocks and for deepening colours, but it can also make a scene look flat and darken clear Australian skies to the point of ultra-violet. It’s important not only to be mindful of where the sun is but also whether a polarised photo is what you want. Great for foliage and cutting out reflections on water, but not so useful when you want to preserve all the golden colours of a sunset. It’s also not useful in shady areas, so there was a whole section of the base-walk where I put it away.

I’ve often thought of Uluru as the rocky heart of Australia, located not too far from Alice Springs. Amazingly, this monolith extends up to 6 km underground, so it’s much like a rocky iceberg. Absolutely worth visiting if you’re ever in a position to do so.