The Fuji Finepix S200EXR was released in 2009. It features:

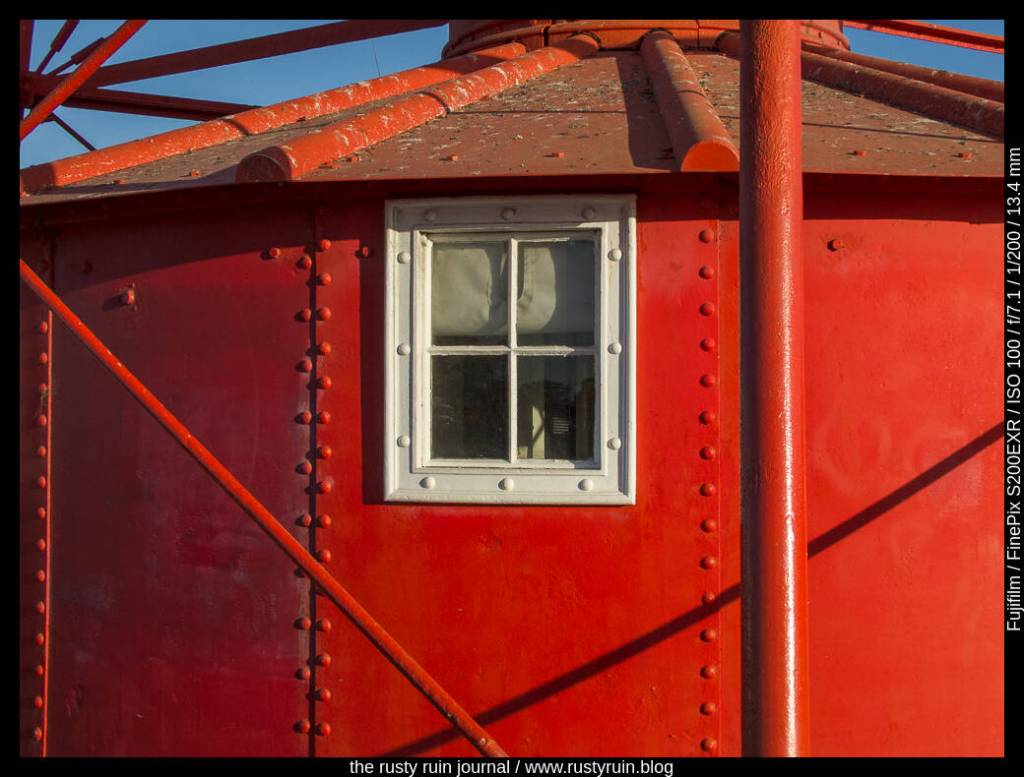

- A 12 megapixel SuperCCDEXR sensor,

- A big optical zoom that starts at 30.5 mm and ends at 436mm (F2.8 to F5.3),

- DSLR-like styling and external buttons,

- A largish, by bridge camera standards, 8x6mm (1/1.6th inch) sensor,

- And a 200 000 dot electronic viewfinder.

In many ways, it feels modern, though the speed of processing is definitely of the 2009 variety. Still, I can save in both JPG and CCD-RAW, unlike previous Fujifilm bridge cameras.

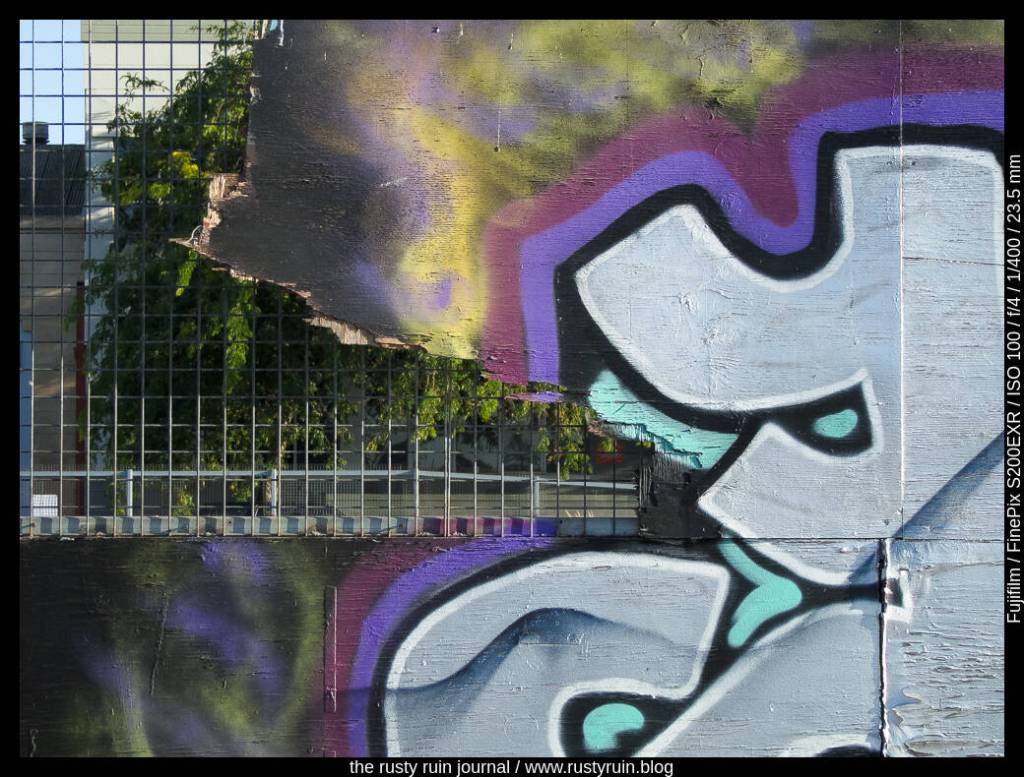

The octagonal pixels that Fujifilm packed into these old sensors might seem odd by today’s standards, but the tech produces photos said to contain extra highlight information. It’s not terribly easy to verify this, as I’m still trying to work out the weird digital alchemy that results in:

- Strange cross-hatch image artifacts in some 12 megapixel images,

- 12 megapixel TIFF files that can only be created from RAF files in an aging program called S7raw – built almost exclusively to read CCD-RAW files from these later Fuji cameras,

- JPGs and RAF files that are 12 megapixels in any of the PASM modes and High Resolution EXR mode, or 6 megapixels in the Dynamic Range or Low Noise EXR modes.

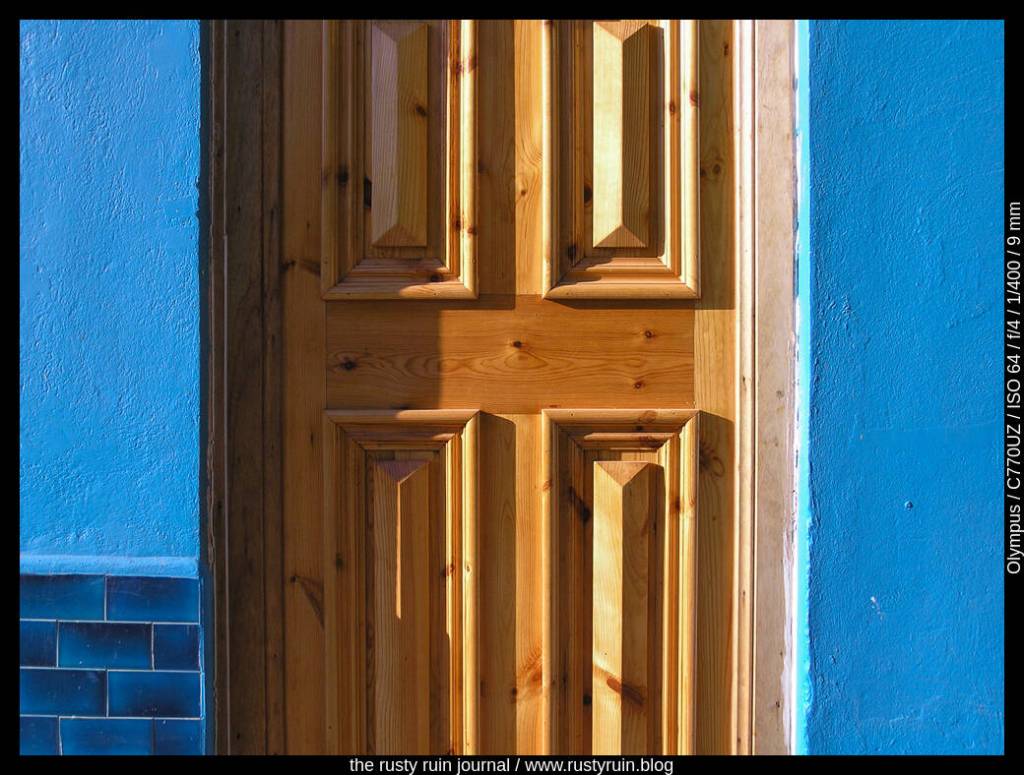

It’s a lot to digest and also explains why some people describe this camera as a JPG machine ~ they clearly have better things to do with their time than mess with TIFF and RAF files. This makes it a complex camera on the inside. And as much as I like that the S200EXR offers classic Fujifilm JPG recipes – Provia, Astia, Velvia, and BW – the menu organisation also reflects the complexity of options available.

The seperate EXR option on the dial offers three special modes: 12 megapixel High Resolution photos that use all of the sensor pixels, 6 megapixel Dynamic Range photos that preserve more detail in shadows and highlights, and 6 megapixel images in the High ISO Low Noise mode. Weirdly, the regular PASM functions don’t offer any of the three EXR special modes and create regular 12 megapixel photos that use a different kind of dynamic range preservation technology.

I’ve found that importing the RAF files into Lightroom is the most convenient option in all cases. The imported 6 megapixel images from RAF files recorded in two of the EXR modes seem to be the darker of two exposures – or at least the darkest part of whatever data lives in the mystical RAF files. It seems likely that Lightroom is throwing away some of the data from the smaller octagonal pixels that preserve extra highlight information. A RAF file recorded in any of the PASM modes results in a 12 megapixel image, and Lightroom imports them just fine – this is my preference going forward.

It seems that the EXR line of cameras represented the pinnacle of Fujifilm’s longstanding SuperCCD sensor technology. Not too long after these premium bridge cameras and their strange alchemical sensors, the company moved to CMOS and their X-Trans technology. Despite the complexities of the camera, I find the images very pleasant.