Some years ago, I made another blog that was about film cameras, vintage lenses, and digital cameras. That blog is long since gone, but having discovered a few recent archived posts, I’m resurrecting some of them:

When Hugo Meyer founded his optical works in 1896 in the town of Gorlitz, little did he know that many of his lenses, including the 30mm wide-angle Lydith lens, would become cult classics in the years following the digital camera revolution. These days, Meyer-Optik Gorlitz lenses are very popular amongst legacy lens enthusiasts and often go for high prices on well-known auction sites. After 1971, Meyer lenses were branded as Pentacon. You can even buy a new and up-to-date Lydith from Meyer-Optik ~ same name but not the same company…that’s brand acquisition and marketing for you.

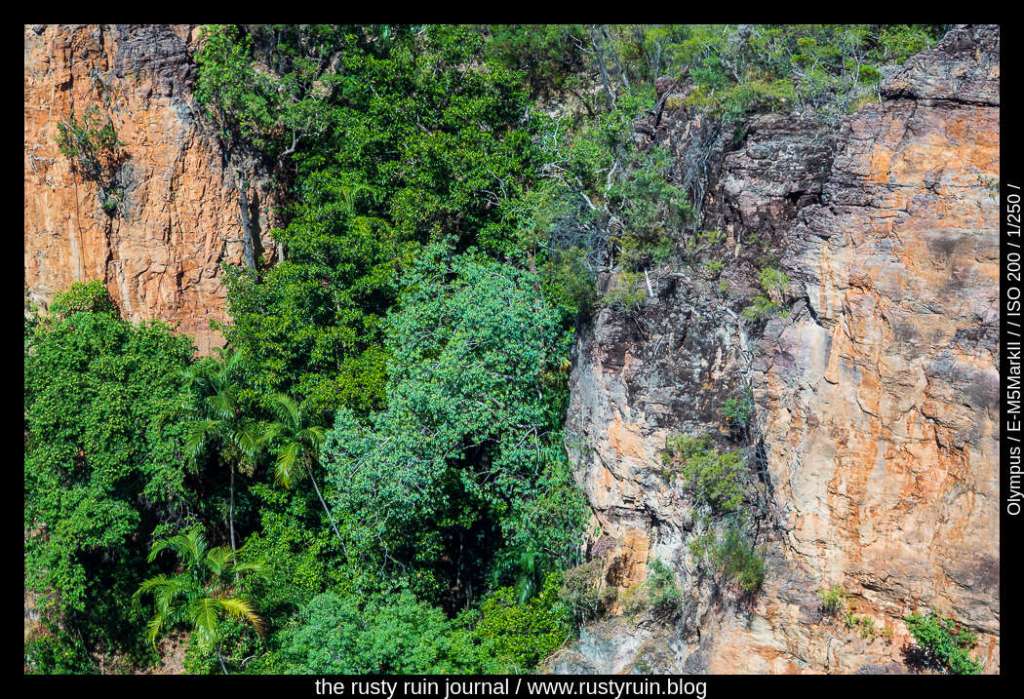

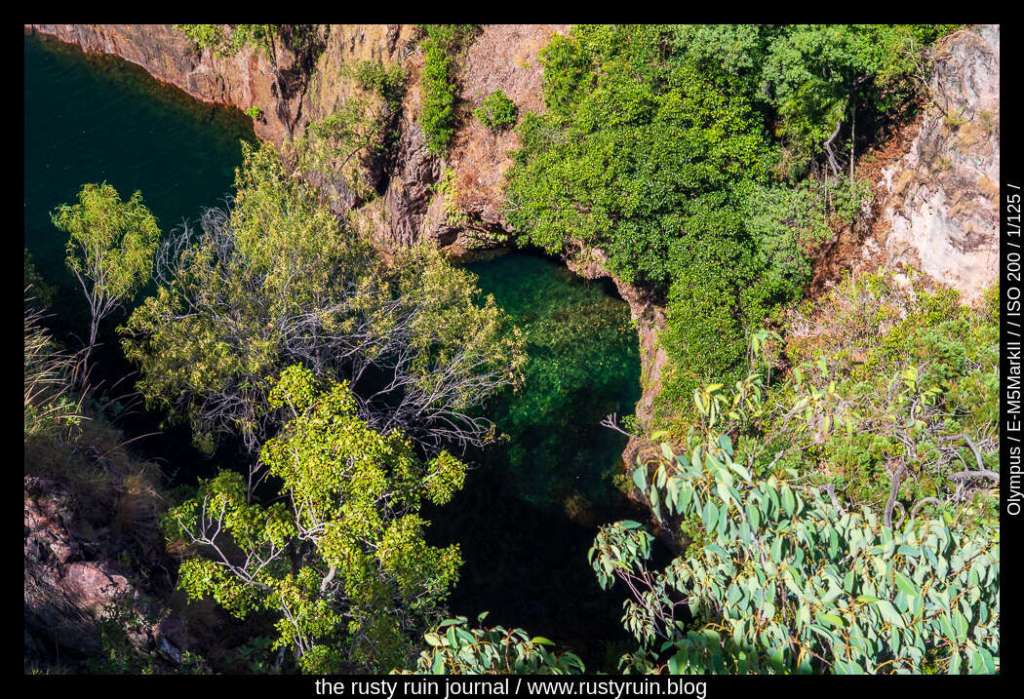

The Lydith 30mm 3.5 lens is not a fast lens. Nor is it especially resistant to flare, due to the early glass coating methods in place at the time of manufacture. But what it lacks in speed and light dispersion qualities, it makes up for in excellent acuity and sharpness.

The Lydith lens is well-made and solid, whilst not being overly heavy, and the zebra pattern adorning the aperture and focus rings on my version make it an attractive lens. The wide 30mm focal length translates to a 60mm field of view on Micro Four Thirds cameras, and a 45mm equivalent field of view on APS-C sensor cameras.

The floral image above demonstrates the centre sharpness of the Lydith. On a crop sensor digital camera, like Micro Four Thirds, the sharpness of the lens will be immeditealy apparent due to the fact that the sensor uses only the central area of the lens. Using such a crop sensor camera with old lenses like this is an advantage if you’re the kind of photographer to whom sharpness is important.

Whilst the Lydith is not especially fast, with 3.5 being the widest aperture, it still produces pleasant and smooth out of focus areas. Edge acuity is generally impressive for such an old lens at the widest aperture setting. The bokeh could be considered distracting, but there’s enough subject seperation to make it acceptable, I think. It’s smooth enough, and background highlights are well rounded. The 10-bladed iris helps. There is also no serious chromatic aberration to speak of from the 5 element Lydith in these samples. These photos are all straight out of the camera JPGs on the Natural colour preset from the Olympus, without additional editing.