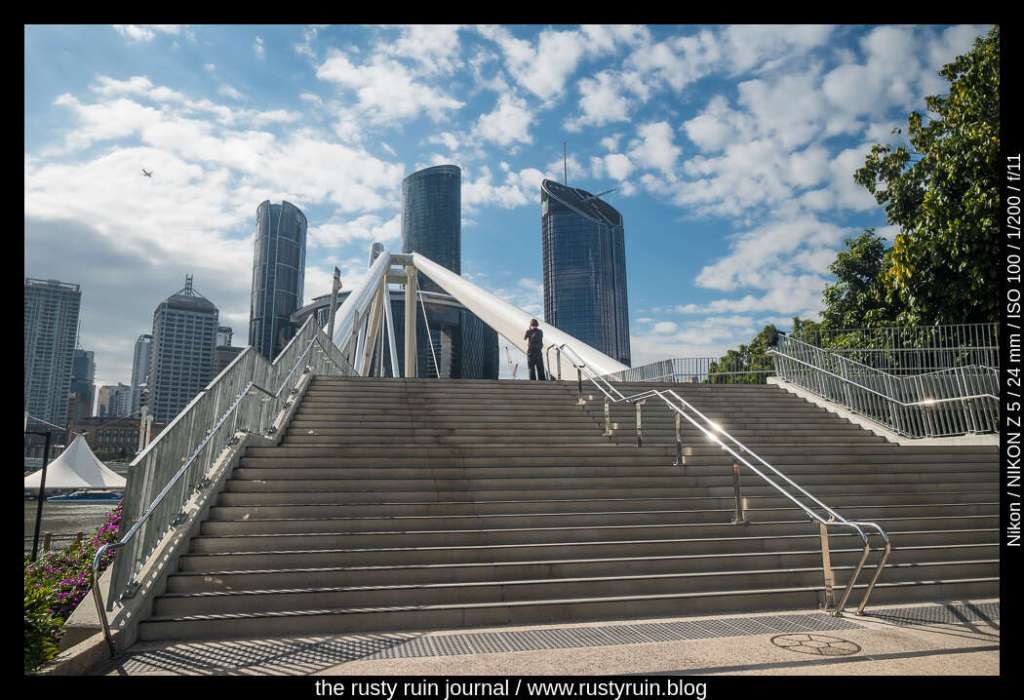

The Nikon D200 and the Kodak Charmera – two very different cameras on the surface. The D200 is built like a magnesium-alloy tank and the Kodak Charmera is a tiny plastic toy. There’s no comparison when talking about image quality, of course, yet I continue to return to the fact that we can freeze time through the use of these devices, whatever their technical limitations.

The act of making a photo has become so culturally habitual – so intertwined with commerce and self-promotion – that the initial magic has long since been lost. We’re a long way from the very first photo made ~ “View from the window at Le Gras”.

It’s strange to think the toy Kodak’s 1.6 megapixels features vastly more resolution than the very first photo made using a camera obscura over an 8 hour exposure time. Marked in technological milestones, human lives seem small. Our lives seem smaller still when we pick up to examine even the dullest stone that lies at the foot of a worn hill that was once a mountain.

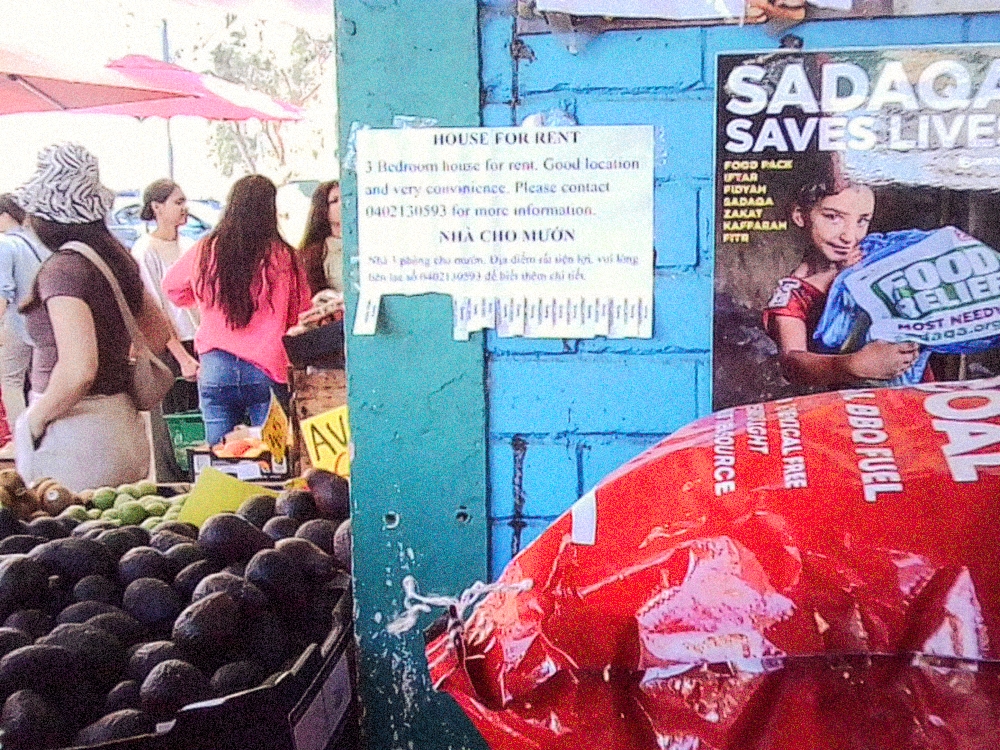

In colour, the photo above is washed out and the highlights burned beyond editing. In black and white, the photo becomes a small study in shape, direction, pattern, and shadow, with a high-key aesthetic. It was a single moment seized as we ordered food.

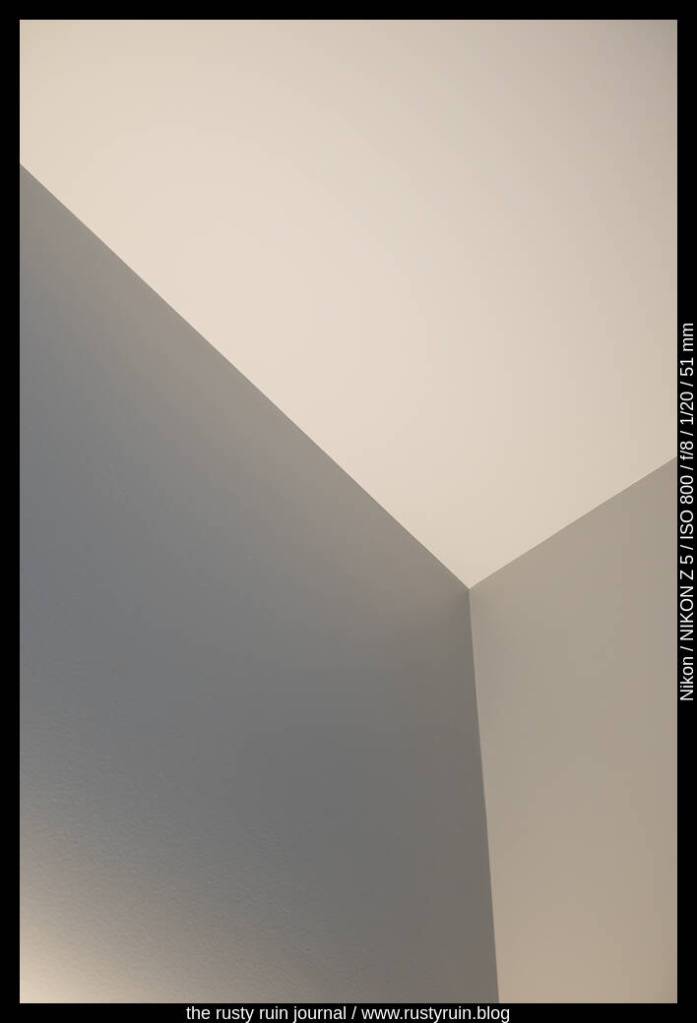

We chanced upon a burned out ruin. I walked around fallen red brick and charred wall cladding, immersing myself in light and shadow.

I couldn’t forget the Nikon D200 in my camera bag. It pulled on my left shoulder as it reminded me that it’s services were available – every bit the prosumer DSLR of 2005 and seemingly so distant from that first photograph in the early 19th century.

One might wonder if there exists a linear technological line between cave art on rough walls and the recording of the world to modern digital storage media? It’s hard to imagine a world without the technology to record ourselves and the world, yet we’ve always sought a type of crude immortality through the things we leave behind – whether recorded on cave walls 60 thousand years ago or posted online. We try to leave a mark before we leave.

Rarely do I have the opportunity to get so close to a ruin like this. Walking over the rubble, the soles of my sneakers adjusting to the sharp edges and angles of detritus, I reflected on the passage of time.