To the local Jawoyn people, the amazing gorges in Nitmiluk National Park (Katherine Gorge) hold special significance. We were fortunate enough to book a short cruise to see some of the many wondrous gorges in the area and view the ancient sandstone rock formations, calm waters, and freshwater crocodiles. This is an area teeming with life and Dreamtime stories.

Sunlight at the height of the Australian afternoon can be harsh. This is one reason I prefer viewfinders rather than the big LCD screens on so many cameras that get washed out in these conditions.

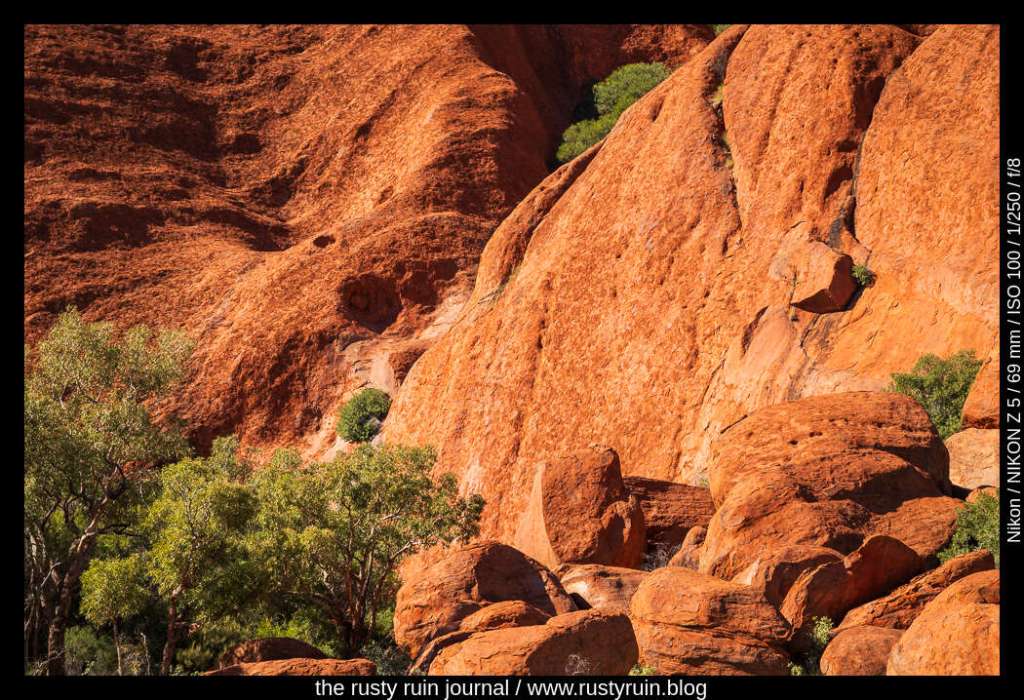

The soft golden light of dawn or dusk brings out the best colours in the outback landscape, but trip timing doesn’t always permit, and you have to work with the tools you have and the light available when the opportunity arises. One quality this strong afternoon light does emphasise: all the textures on the ancient sandstone.

On the day, I packed lightly since I’d been lugging a not insignificant amount of camera gear around on other days (hello Lowepro Nova 200). The Olympus EM5 provides good image quality and lots of control in a small package. It’s just a small pity I’d also decided to take the 14-42 kit lens with me. That’s not to say that kit lenses are bad at all. Nikon makes some great kit lenses, such as the 18-55mm. And this Olympus Zuiko kit lens is no slouch in the image quality stakes – it does pretty well for a cheapish plastic lens. But at times when I want more sharpness to record all of the landscape’s details, it gets a bit fluffy and squishy at the edges of the frame. Still, you work with what you have and the conditions of the day.

I’ll always say that eye-watering sharpness is generally overrated in photography, but there are times when sharpness is another tool you want in order to communicate certain qualities – the texture of the rocks in this case. Despite some of the shortcomings of my kit lens, careful subject selection, use of exposure compensation to retain as much detail as possible in high dynamic range scenes, and some boost to the red/orange/yellow colour channels during editing helps to make the photos shine. I also reduced highlights to reveal the details of the ancient sandstone.

As the clouds grew heavy, the light conditions became a little more forgiving. As you can see in the above photo, clearing clouds also provided an opportunity to record sunlight as it illuminated sections of rock. I used the so-called plastic fantastic 40-150mm Olympus Zuiko lens for this photo – small, light, and really quite sharp at most focal lengths. I guess the message is to know your camera gear and accept and make best use of your tools and the conditions. I’ll freely admit to not knowing all of my gear well enough at times!