If you believe the more scurrilous online rumours, the quality of a camera lens from the former Soviet Union was directly proportional to the Vodka consumption of weary factory workers. This is not the colourful fancy one might suppose, as any factory line embedded in an economic and socio-political culture where wages are neither incentive nor punishment is more likely to be driven by exhausted hands and eyes.

None of this suggests that any cheap trinket or fast fashionable piece made today in vast factory cities by exploited workers and then sent abroad to be marked up for huge profits is any better. Always, there are grifters and exploiters taking advantage of the vulnerable and the gullible. But anyway…I digress slightly. The source of my Soviet-produced lens beyond the factory floor is not a story for today.

The Zenitar 16mm 2.8 Fisheye lens is an impressive piece of Cold War glass. It’s a hefty thing in the hands, has a distinct and very short hood, a lens cap that can’t be used on any other lens, and looks great when the sunlight bounces off the large curved glass that sits right out front. On my trusty Olympus EM5 Mark 2, this 16mm Zenitar has a field of view equivalent to a 32mm focal length in 35mm format. So, if I was using it on my Z5, which has a 35mm sensor, the field of view is the native 16mm. Because my Olympus has a digital sensor that’s half the size of the one in my Z5, I double the 16mm to a field of view of 32mm instead.

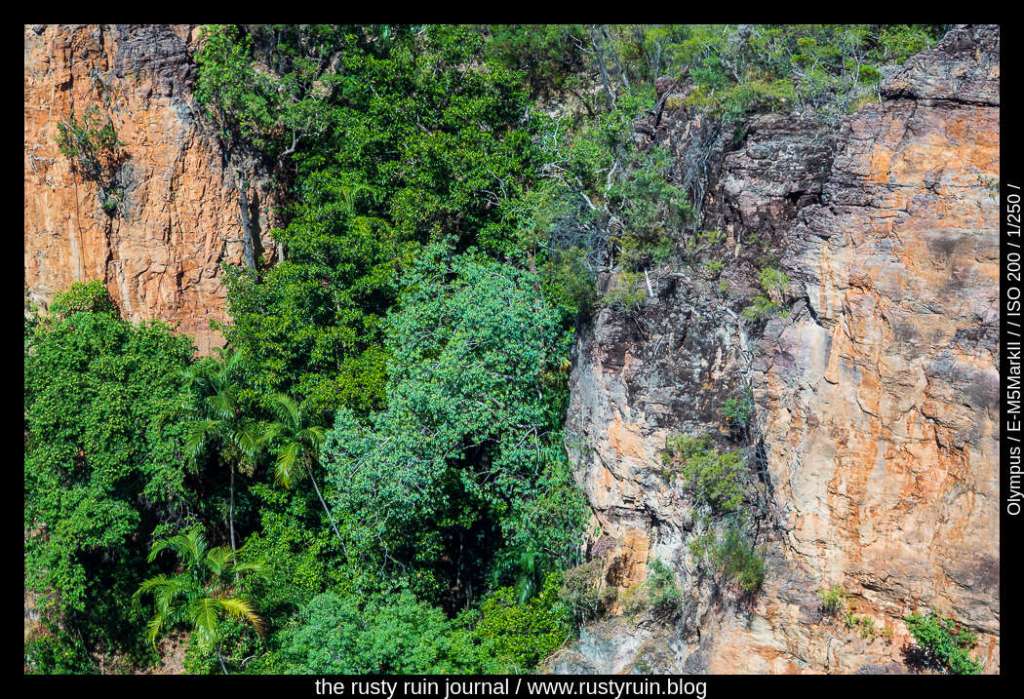

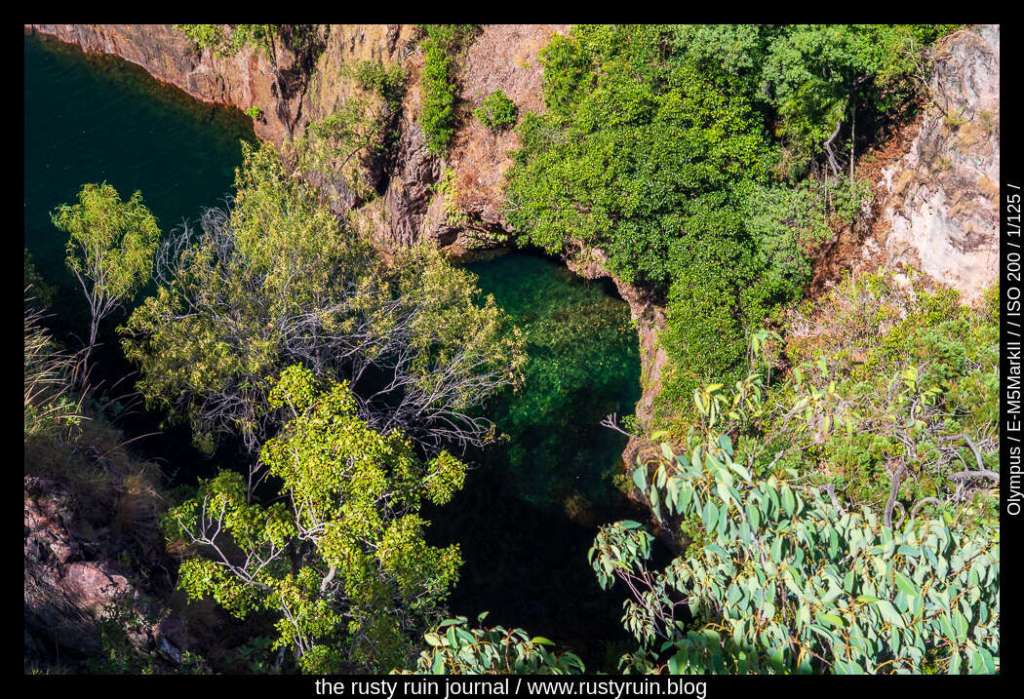

My copy of the lens is sharp enough at apertures F 5.6-8, and even at those settings the corners display a lack of sharpness that’s more fizzy than actually mushy – as though details are being pulled away from the centre and slightly distorted. The effect reminds me of using a plastic lens but I don’t find it unpleasant.

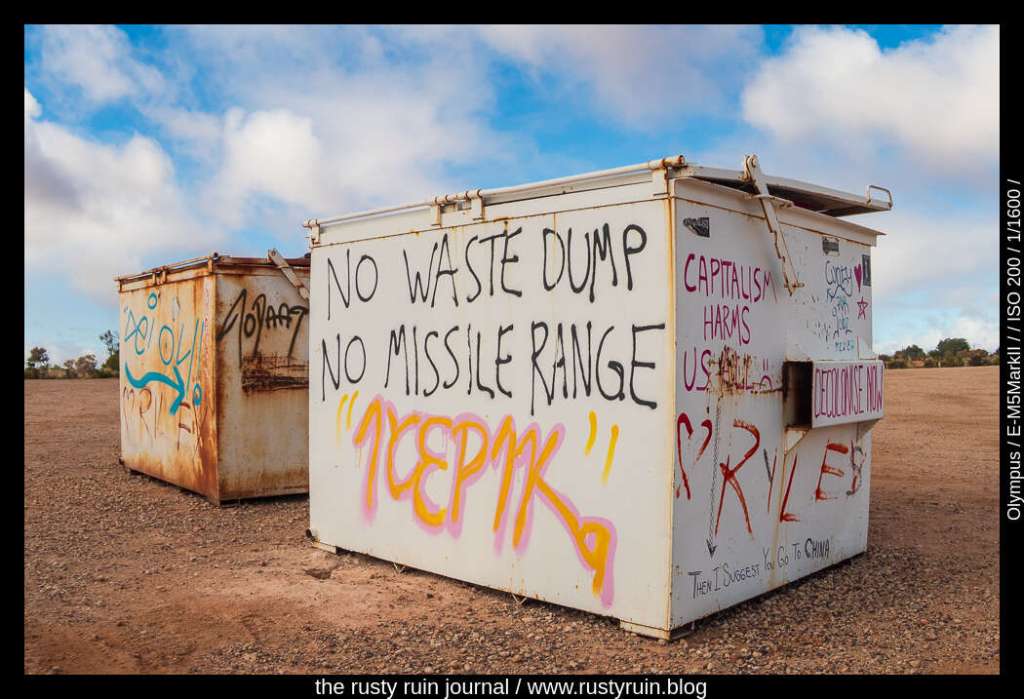

As with other wide angles, and certainly with all Fisheye lenses, there’s distortion. You can see how the normally straight cortners of the skip bins in the above photo look bowed. I don’t have an issue with it, as this is just a feature of the lens, but it’s not the sort of lens you want if you desire pleasant portraits, straight horizons, and distortion-free buildings (using the Nikkor 16mm 2.8 lens profile in Lightroom will straighten out most of the distortion if you really want that).

Lenses like this are great for getting in very close to a subject to take advantage of the optical distortions they produce. On the Olympus, however, the Fisheye effect is certainly much less because of the smaller sensor size, making it a really valuable wide-angle lens if you don’t mind manual focus, fizzy corners, and the chance that the quality of your copy may have suffered due to the effects of authoritarianism and the revolutionary whims of Vladimir Lenin.