If you hang around in online photography forums, especially where beginners flock, you’ll come across people proclaiming that the best and only way to really learn photography is to set the camera dial to Manual Mode and endure the suffering until it makes sense. I think this is one of the worst pieces of advice that anyone can give to a beginning photographer!

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that Manual mode is bad or inferior. Of course it’s not. Some beginners might even learn well by pushing through the disappointment of fumbling with sweaty command dials whilst missing photographic opportunities. It’s just one way of learning, and everyone learns differently.

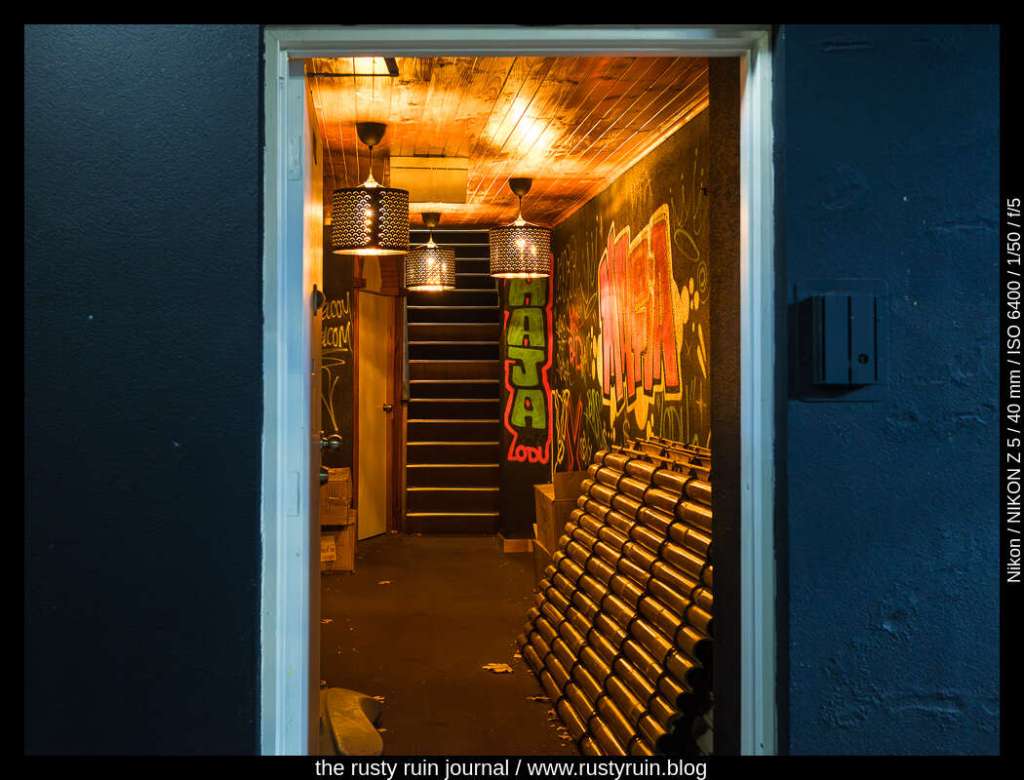

In fact, I heartily recommend Manual mode and night photography to any beginner who wants to learn all about the role of light in photography and how it can be controlled through shutter speed. What I object to is the stubborn declaration by some photographers that Manual mode is the Holy Grail and will enlighten even the most confused beginner. Let me tell you, setting that dial to M is more likely going to frustrate an eager beginner and turn them sour.

Learning about the exposure triangle – how Shutter Speed, Aperture, and ISO interact to control light – is essential in the journey, but it’s not a mad race to the finish line. Rather than stopping stubbornly at M and staying there, set the camera to Aperture or Shutter Priority mode and take the gentler path. There’s no shame in using any of these modes. Set it to Auto or Program mode, even, and concentrate on developing the eye and the imagination and living in the moment. There’s NO rule that states a photographer must use Manual mode all the time, every time. Cameras are tools that provide options and we use the best tool for the job to produce a result.

Photography is about more than gear. It’s about more than the money you spend. It’s about more than how sharp a lens is or how proficient you are at reading a light meter – and lets face it, insecure ego-driven types who are stuck in M are likely still glued to their camera’s inbuilt light meter anyway – even old film professionals use a light meter as a starting point.

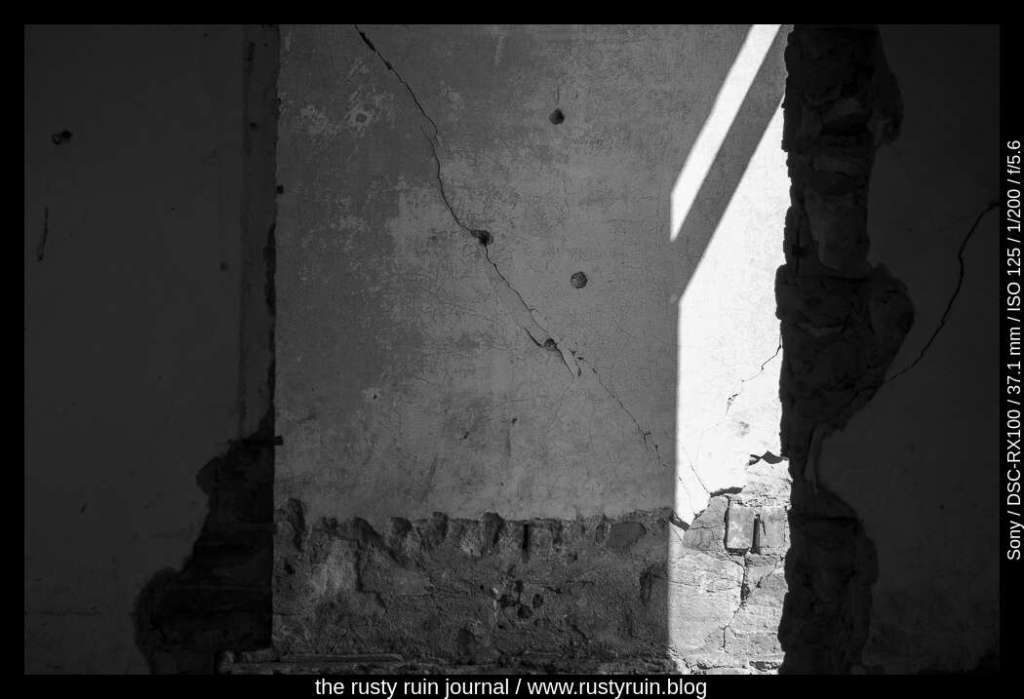

The truth is that lots of mediocre photographs are made in all camera modes. There are people obsessed with sharpness and eradicating all digital noise, but forget that an interesting composition is key. There are also people justifying the thousands spent on gear, hoping their next pro camera body purchase will make them a better photographer. Let me tell you something: if you make mediocre photos on a 16 megapixel camera, that 45 megapixel camera on the shop shelf isn’t going to suddenly make you better. Getting better is not just about becoming technically comfortable. It’s also about learning to see the world differently.